Visual anthropology competition

Congratulations to our Visual Anthropology winners for 2025!

Please enjoy our virtual exhibition below:

Every year, ANSA holds a visual anthropology competition open to all ANSA and AAS members. Our aim is to celebrate creativity in anthropology, and give space for emerging scholars to showcase their work. Winners will receive a cash prize and have their work displayed at the AAS conference in June 2026

For the 12th annual competition, we ask for entries that reflect on the ways in which creativity and visual practice have helped you with your fieldwork and ethnographic practice.

2025 visual anthropology competition winners

First place:

ngaire dowse

“grounds of resistance” AND “woven country”

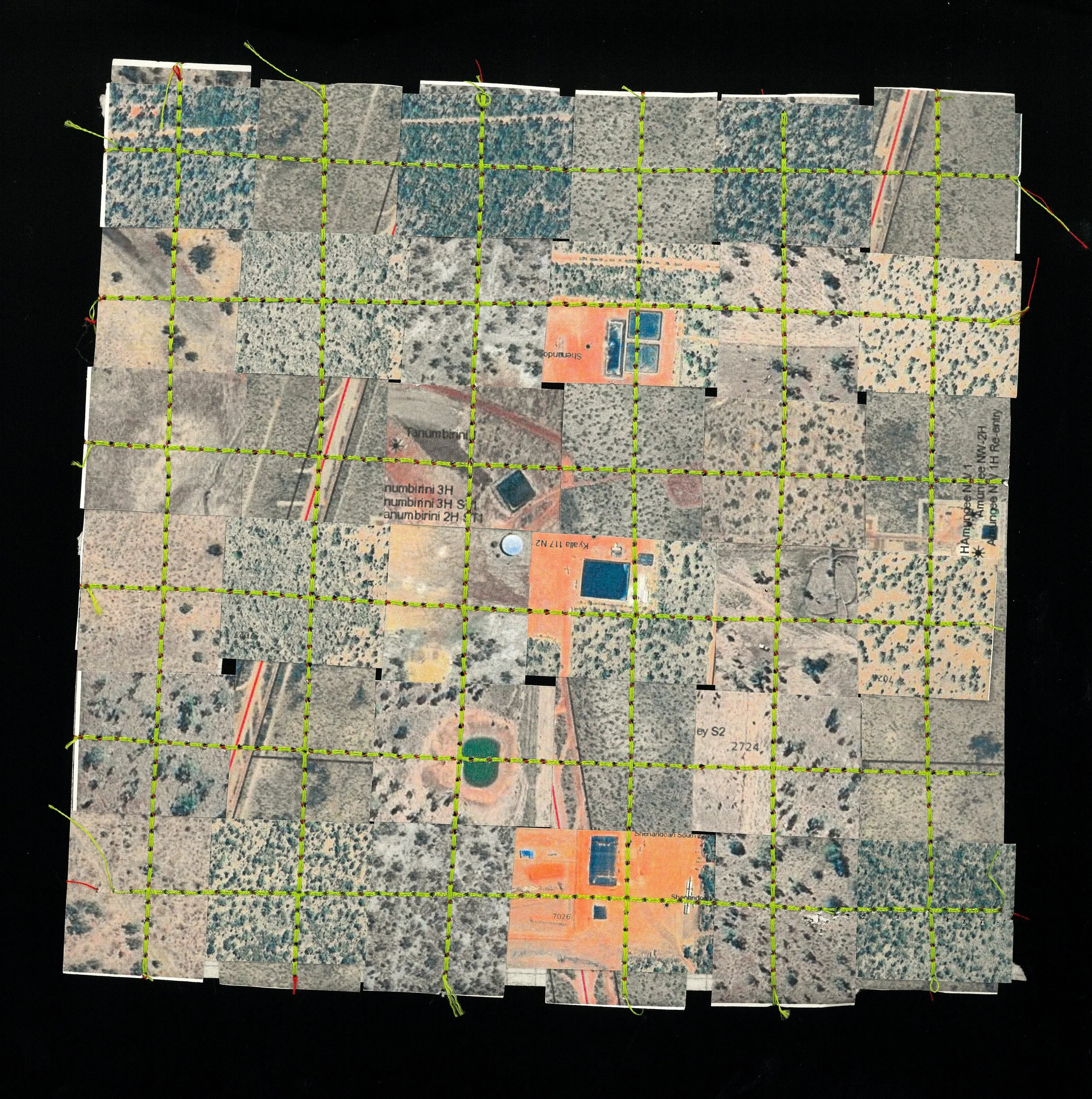

Title: Woven Country (2025)

This work is composed of satellite images of fracking wells across the Beetaloo Basin in the Northern Territory, which I have printed, cut, woven, and stitched together into a patchwork. The images represent a rewriting of the landscape, a point where relations are interrupted, yet the stitched seams gesture toward repair, care, and reconnection.

Thinking with Deborah Bird Rose’s (2024) writings on Wild Country and Quiet Country, I consider the tensions of rupture and repair taking place on Country. Rose argues that Quiet Country is not a state of lifelessness but one of care, where human and non-human responsibilities that sustain life are fulfilled. Wild Country, by contrast, emerges when those obligations are broken through ecological disturbance and colonial neglect. The fracking wells visible in the satellite images mark such disturbances, showing a landscape rendered “wild” and “silenced” by extraction, stripped of its liveliness and vitality. By re-stitching these ruptured images, I aim to evoke the efforts of my research participants who engage in “quieting” Country, not to silence it, but to listen again to its calls for care.

Satellite imagery allows us to see the scale of fracking sites, but it is also a way of seeing that separates the observer from their place on and in Country. This contrasts with the grounded and embodied ways of knowing described by Rose’s teachers and by my own research participants. Through this juxtaposition, I explore how Country is understood both as “nourishing terrain” and as a resource available for extraction.

This contrast also relates to my reflections on the ethnographer’s task of holding multiple perspectives without collapsing them into a single frame. The act of weaving and stitching these elements together becomes a visual and methodological expression of this process. The patchwork reflects not only the contradictions visible on the land—extraction and care, damage and repair—but also the contradictions within ethnographic work itself.

Just as fracking alters Country to reach what lies beneath, anthropology has often opened communities to extract their stories, cosmologies, and lives for analysis. The ethnographer, like the fracker, comes to know through penetration, by entering, recording, and rendering visible what was once hidden. The question that guides this work is how one might study the effects of extractivism without reproducing its logic.

I draw on Rose’s understanding of relational ethics, which she describes as central to living with Country, an ethics of attentiveness, repair, and responsibility in the face of ecological loss. In my fieldwork, I have witnessed both the destructive impacts of resource extraction and the generative alliances that form in response—between Traditional Owners, activists, scientists, and others who work together to care for Country. The woven and stitched images mirror this duality, where the carved-up land and the act of mending coexist.

As an ethnographer, I inhabit a similar paradoxical space. I participate in acts of care, advocacy, and collaboration, yet I am also situated within an academic system that values knowledge as something to be produced, circulated, and ultimately extracted. This work therefore stands as both a reflection and a commitment: an effort to practice anthropology as an act of mending, rather than one of taking.

Reference:

Rose, D. B. (2024). Dreaming Ecology: Nomadics and Indigenous Ecological Knowledge, Victoria River, Northern Australia (D. Lewis & M. Jolly, Eds.; First edition.). ANU Press.

Title: Grounds of Resistance (2025)

Grounds of Resistance is a collage composed of photographs and paper fragments gathered during fieldwork with communities opposing hydraulic fracturing in the Beetaloo Basin, Northern Territory. The work brings together images of protest signs, landscapes, people, and animals – visual traces of a shared struggle for land, water, and recognition. Its overlapping and uneven structure mirrors the complex terrain of relations in which these struggles unfold. The assemblage gestures toward what Francesca Merlan (1998, 2005, 2013) describes as the intercultural domain: not a meeting of discrete cultural worlds, but an ongoing, dynamic condition of coexistence and negotiation, shaped by historical inequalities and shared engagements with place.

This piece explores the entangled processes through which relationships to Country are enacted, negotiated, and contested. In the Beetaloo, alliances between Traditional Owners, environmental activists, pastoralists, and scientists have been forged through shared, albeit uneven, vulnerability to extraction and a common commitment to the more-than-human world. The collage visualises these relations as a heterogeneous gathering, where care for Country emerges from collaboration across lines of difference. Grounds of Resistance thus reflects the intercultural entanglements that define much of the environmental politics in northern Australia: moments where people come together across difference to protect Country, even as they navigate the enduring legacies of colonisation and resource extraction.

I use this piece to resist a singular, authoritative narrative and to give weight instead to layered, partial perspectives: Indigenous custodianship, environmental activism, bureaucratic governance, and Western scientific thought, none of which can claim Epistemic certainty. The work also reflects the contradictions of ethnographic practice itself. As an anthropologist, I grapple with my own capacity to interpret and represent others while acknowledging that no interpretation is ever free from one’s own worldview. Ethnographic practice, like this collage, assembles meaning from fragments, always aware that something remains lost or silenced in the process.

Ultimately, the work resonates with Merlan’s (2005) argument that the intercultural is not a transitional space but the ordinary condition of life in settler-colonial Australia, one marked by both mutual recognition and enduring asymmetry. This tension becomes visible in the collage through points of disjuncture, where images and ideas fail to align neatly and meanings resist full translation.

RunnerS up

Elizabeth Scarfe

Title: basement lives

A grid collage of 16 street-level basement windows in domestic buildings around central Reykjavik, August 2025. The selection of windows shows diverse strategies for achieving varying levels of privacy, including plastic frosting, blinds and curtains, and stick-on lead lighting decals. The windows contain a variety of visible items, some decorative displays, both personal ephemera and impersonal ornamentation, some functional storage, and some political statement. The images also show a range of building materials, window designs, and external use of colour. One of the images is a still from a tracking app video of the route walked.

I spent my first week in the field in Reykjavik, before moving to the rural farming community that would be my primary field site. Walking the city streets, my attention was caught by these semi-subterranean rooms, the windows often affording an intimate view into people’s homes. From this curiosity, I devised a small visual anthropology project in which I spent a day walking the city streets, photographing these windows and documenting my reflections on the ethics, methods, and anthropological theories that arose as I considered the different windows. I also used a phone app to track the route, with the functionality to create a three-dimensional video map of the route.

Whilst I can’t foresee directly using the data at this stage, the activity proved incredibly generative as a thinking activity. As the walk progressed, I reflected on the selection criteria I was using to decide which windows to photograph. I was initially excluding windows with ‘nothing’ in them, and windows with internal concealment, thinking them ‘uninteresting’. Questioning my own exclusion criteria prompted reflections on how Icelanders are navigating public-private spatial performance through their use of window coverings. It also helped me reflect on whether my photography was an invasion of privacy or not, and as I went along, I improvised an ethic for what I would or wouldn’t photograph, myself trying to navigate what are obviously private spaces but on public display. Just because we can see, doesn’t mean we should look, invoking a curiosity about what Icelanders agree not to see. Despite seeing and photographing both being forms of capturing visual data, the appropriateness of one and not the other further entangles notions of public and private when we consider what the use of recording devices can mean for the distribution of visual data.

The project also made me reflect on the Icelandic narrative of being a classless society, a narrative ruptured by the 2008 financial crisis. Whilst class is more complex than financial resources, the significant difference in housing standards from one street to another made me both curious and confused as to how and why the classlessness narrative persisted amidst such obvious economic disparity, connecting back to the notion of what a culture agrees not to see.

By studying fifty different window images, I developed a typology of basement window performances, determined by the repetition of items on display. At the time, I thought this might provide some insights into the domestic spaces of everyday Icelanders, however, since taking the photos, I have been inside at least five Icelandic homes and suspect this isn’t the case. The complexity and personal nature of what fills Icelandic homes was not hinted at by what I saw in the windows.

Kylie Dolan

Title: Taking photos at New Sub, Maningrida

On my last night of fieldwork, I fetched Erin from a card game. As we left, she whispered, “When they not looking, take it secret one.” Cards had been a curious taboo in my time living with Erin, with whom I did almost everything else. When cards called, she dumped me at home with the oldies and played through the night. Cards was an activity of “all the sinners” and she wasn’t willing to “spoil” or corrupt me – or her reputation – should she be seen leading me there. Her instruction to take a secret photo of the game brought so much to light: her wish to include me in some way; the restrictions on my being there.

But I was welcomed to photograph freely when we hunted on the weekends. People were strikingly at ease being photographed on boats, along the beach, making fires, plucking pandanus, wielding handlines, spears, nets, and knives. I was asked to photograph and record several ceremonies. I was ambivalent about this initially, particularly at closed or private ceremonies, but the prints I’d make in Darwin were much desired. It seemed that taking photos in these contexts continued a tradition of visual ethnography in which parts of customary and cultural life have been documented for decades.

There was a rough split between the type of camera I used and the type of content it captured. My DSLR became the camera for ‘high culture’: hunting and ceremonies; my phone camera for everyday moments around the house and kids’ hilarity. Much like everybody else’s smartphone, this was the one young girls returned to me with a thousand selfies.

That split was also expressed geographically. At New Sub, where I lived with Erin, the DSLR lay mostly idle. New Sub is Maningrida’s 15-year-old housing development, home exclusively to Aboriginal residents. New Sub was “too hot,” “too loud,” “got no culture,” and its residents, as they habitually said, were “all mixed up.” They neighbour people they hardly know, a very different situation from the main town, where since the 1950s camps had formed in language group clusters. On that side of town, I would be told to “Come, bring your [big] camera,” when a ground oven was being dug, a catch was in, when a funeral or ceremony was held. But few of those activities took place at New Sub. There, burials are prohibited, and the lack of time-honoured shared spaces, ceremony grounds – and nearby family to organise with – seem to function as de facto prohibitions.

Whether or not I took photos, and on which camera, said a lot about the kind of activity taking place and how people felt about it. Noticing this has helped me recognise a new cultural politics playing out in Maningrida – and at New Sub. I realise I have almost no DSLR photos of life at New Sub. This has brought home to me that for many people living there, there is less to celebrate, document, or memorialise – at least by an anthropologist.